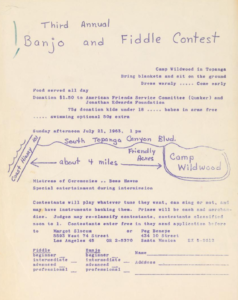

We recently discovered the winners list and flyer from the 1963 Topanga Banjo Fiddle Contest, which was 60 years ago this year (2023). The Topanga Banjo Fiddle Contest is one of the oldest traditional music and folk arts festival in the US and 1963 was already its third annual event.

These two sheets come from the papers of Bess Lomax Hawes and together with a registration list are about all the documentation from the early years of the Topanga Banjo Fiddle Festival. Even those only exist because she was a collector (just like her folklorist father and brother, John and Alan Lomax). The flyers were created using a ditto machine. I remember the faintly sweet, headache-inducing smell of pages fresh from the duplicating process, a feature of school life still in the 1970s. Now an obsolete and really not missed technology.

Bess was the MC for the 1963 event, then still at its original location. She had moved to Los Angeles in 1951 and helped catalyze the folk music revival of the 1950s and 1960s locally. Bess became professor of Anthropology at Cal State Northridge and later worked for the Smithsonian and National Endowment of the Arts. As a songwriter (with Jackie Steiner), Bess had an unexpected hit: The MTA song, originally written for left-wing candidate Walter A. O’Brien’s 1949 political campaign, was revived by the Kingston Trio in 1959, first as a single and later on the Kingston Trio’s At Large album. The Kingston Trio changed the politician’s name to avoid association with a party perceived as communist sympathizers. Without Walter O’Brien’s name holding it back (it was the Red Scare period), the single reached number fifteen on the Billboard chart, and the album reached number one on the pop charts, won a Grammy, and remained charted for over two years. The storyline is about a Charlie trapped in the Boston metro system as he cannot pay the exit fare. Nowadays, the subway card in Boston is named the ‘Charlie Card’ in honor of the song. As appropriate for the folk tradition, it is based on a traditional tune (earlier versions would be “The Ship That Never Returned” and then the steam-power era “Wreck of the Old ‘97”). The lyrics give a nod to its ancestors with the line of “he’s the man who never returned”.

Angeles in 1951 and helped catalyze the folk music revival of the 1950s and 1960s locally. Bess became professor of Anthropology at Cal State Northridge and later worked for the Smithsonian and National Endowment of the Arts. As a songwriter (with Jackie Steiner), Bess had an unexpected hit: The MTA song, originally written for left-wing candidate Walter A. O’Brien’s 1949 political campaign, was revived by the Kingston Trio in 1959, first as a single and later on the Kingston Trio’s At Large album. The Kingston Trio changed the politician’s name to avoid association with a party perceived as communist sympathizers. Without Walter O’Brien’s name holding it back (it was the Red Scare period), the single reached number fifteen on the Billboard chart, and the album reached number one on the pop charts, won a Grammy, and remained charted for over two years. The storyline is about a Charlie trapped in the Boston metro system as he cannot pay the exit fare. Nowadays, the subway card in Boston is named the ‘Charlie Card’ in honor of the song. As appropriate for the folk tradition, it is based on a traditional tune (earlier versions would be “The Ship That Never Returned” and then the steam-power era “Wreck of the Old ‘97”). The lyrics give a nod to its ancestors with the line of “he’s the man who never returned”.

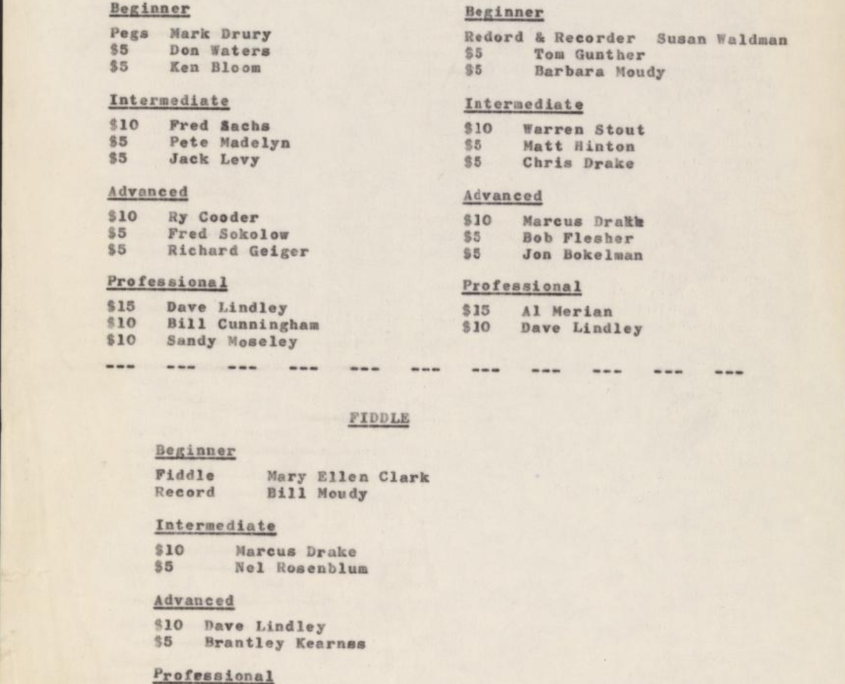

The Topanga Contest winner’s list from 1963 shows the astonishing depth of the LA scene. You’ll recognize quite a few of the names, even though serious contestants tend to fall into a very compressed age range. Almost all of them were teenagers, Richard Greene may have been the senior among the serious contestants, at age 20 (but then he had already won the two prior Topanga contests). Several, like Ry Cooder, were still in high school. David Lindley was particularly eager, entering every category. Other contestants were older. Mary Ellen Clark, in beginning fiddle then, was Bess Hawes age.

Other than those sheets, information about the early years lives in the participants’ memories, though those have become quite hazy (at best). Ken Bloom told me

Ken Bloom

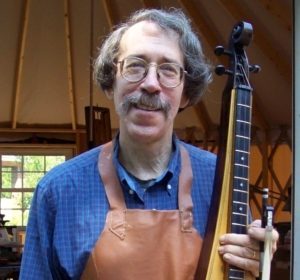

“I don’t remember much in the way of specifics about the contest. There was a whole community developing around our common interest in folk music and more specifically Oldtime and Bluegrass music. I just remember that we all helped each other unravel the mysteries of the music. It certainly affected our later lives. It was an exciting time.” Ken mostly stuck with the trad music and in the 90s dedicated himself to building, teaching, and performing bowed dulcimer.

Richard Greene was in the middle of a streak of winning the fiddle category in 1963. While TBFC had a “professional” category, that was more an aspirational designation than reality.

Dry City Scat Band 1964: David Lindley, Peter Madlem, Richard Greene, Steve Cahill. (Madlem is misspelled on the 1963 winners list as Madelyn).

Various combinations of bands involving the core contestants came and went, including the Dry City Scat Band, which modestly called itself “the band that made bluegrass obsolete”.

Richard surely had to roll back that claim quickly in order to become a member of Bill Monroe’s Bluegrass Boys in 1966, which was his entry to broader recognition. After some electric adventures, he returned to acoustic music of the “New Grass” or “New Acoustic” instrumental music flavor. Richard has been at TBFC repeatedly since, especially in the last 20 years when several of his students won the advanced fiddle category. And his influence has been traced in an academic article, entitled: The Diffusion of an Instrumental Technique across North Atlantic Fiddling Traditions

Not everybody was that excited about bluegrass or at least they had other priorities at that time, like Ry Cooder, winner of the advanced bluegrass banjo category in 1963: “I had a 60’s solid tone ring archtop Mastertone that was so loud it gave me headaches. I sold it for $300 and bought a 1947 Packard super clipper sedan.”

Mary Ellen Clark (then still only in her 80s) and Anya Sturm, oldest and youngest members of the Scottish Fiddlers of Los Angeles.

Mary Ellen Clark would later run the Topanga Banjo Fiddle Festival in the 1960s and she continued to participate in community folk groups well into her 90s. She was not too much into tuning or replacing strings, occasionally I brought her guitar back into roughly standard pitch. Very gingerly – the strings were decades old. For all I know, Pete Seeger might have put them on.

After having jogged his memory, Ken Bloom had a follow up on the 1963 contest: “I do remember Lindley playing the most amazing version of the Arkansas Traveler you ever heard. Started out only using his left hand for a couple of times through the tune so when his right hand crashed into the banjo it was pretty dramatic. He always did have this Quixotic sense of humor.”

Two other 1963 contestants show up regularly at the event these days. Brantley Kearns, who took second to David Lindley in the advanced fiddle category, probably is best known as the fiddler of Dwight Yoakam’s band, but obviously plays all genres (and also is an actor). I saw him at last year’s festival; until recently he volunteered for the chore of being a judge (a lot of sitting!). Fred Sokolow, second to Ry Cooder in 1963 in advanced bluegrass banjo, is almost certainly the most published author of instruction materials among this group, probably has done more than 100 books.

Ry Cooder’s Giant Fairbanks ca 1900

Ry Cooder didn’t abandon the banjo, in fact, he plays one on his latest recording with Taj Mahal (another 1960’s TBFC alumnus) that won a Grammy a few weeks ago (February 2023) for best traditional blues album: Get on Board: The Songs of Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee. At the opposite tonal spectrum from the head-ache inducing Mastertone he traded for a car in the 1960s, a very dark thuddy sound. And in an unexpected place, a funk line on Packing Up. I wasn’t even sure it was a banjo, but when I asked Ry, he responded with the picture on the right. He also said: “I was never headed for high banjo status. There were guys way further ahead, even on the west coast, so i backed off. We can’t all be J.D. Crowe. These days, i play banjo ok, but back then there was no future in it.”

Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee bring us back to Bess Hawes. Bess Hawes and her husband were members of the Almanac Singers in New York with Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger. Their Almanac House (an apartment actually) became a center for leftist intellectuals as well as crash pad for folksingers. In 1942, that included a new duo of Blues musicians who wanted to break away from their genre and do something “modern” in the big city (like jump blues): Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee. Eventually they found more success sticking with their roots because that was in demand in the 1960s. Terry and McGhee (along with Bill Monroe, Tommy Jarrell) were recipients of the inaugural National Heritage Fellowship in 1982, the United States government’s highest honor in folk and traditional arts. The founder of the National Heritage Fellowships? Bess Hawes.